Executive Summary

At the start of the human tragedy that is the Ukraine war, I delved into the underlying causes of the conflict from the perspective of a historian and political scientist. That analysis, “Understanding The Great Game in Ukraine,” is available here.

Events have progressed since then, and an important fallout of the war has been economic. In this article, I look at the role and situation of Europe from the perspective of an economist.

The European Union has taken a very definite political stance on the Russia-Ukraine conflict, aligned with the United States. It has applied 8 rounds of economic sanctions against Russia, and at the time of writing, is working on a 9th package.

What has the economic impact of these sanctions been - on Russia and on Europe itself? What will happen in the months to come? That is the focus of the present article. I conclude that

- The war in Ukraine that started on February 24, 2022, is going to be the most consequential change in the world since the Second World War. It is going to fundamentally change power relationships in the world. The dominance of the Western world will end and be replaced by a multipolar world.

- Europe’s prosperity of the past few centuries is likely to end because of short-sighted and poorly-thought-out decisions related to the Ukraine conflict, taken by European leaders with the full support of their people. These have to do primarily with the ill-considered economic sanctions that Europe has unilaterally applied on Russia, that have started to boomerang on Europe, with the high probability of things getting much worse in the coming months.

The analysis presented here is primarily an economic one, and mainly looks at the effect on the economies of Europe of prolonged sanctions (and, in the present context, “prolonged” could even mean another six months) imposed by the West on Russia.

I present evidence that makes the case that Western sanctions on Russia have hurt Europe a lot more than they have hurt Russia in the nine months since they were imposed, and in the coming months will continue to severely degrade Europe’s economies, while only marginally affecting Russia’s. The primary reason for this is that Russia is far more self-sufficient than Europe is. The only action that will save Europe is an unconditional revocation of its self-destructive sanctions and a peace agreement in Ukraine on Russia's terms.

The only major assumptions I have made in this analysis are that, in the next two to three months,

- The war in Ukraine does not end in complete defeat for Russia

- Ukraine and Russia do not reach a peace agreement, and

- Vladimir Putin is not ousted in a coup in Russia — and hence, the current economic and military policies of both Europe and Russia will continue for the foreseeable future.

Although Russia looks unlikely to be affected very significantly by Western sanctions, and is in a strong position on the battlefield, because of its high inherent economic and military strength (recent reported gains by Ukraine notwithstanding), I argue that in the unlikely case event that Russia were to appear likely to lose the war on the battlefield or on the economic front, China will do whatever it takes to prevent such outcomes, to secure its own future.

This essay is organized in six chapters, followed by a summary and conclusions chapter:

- Chapter I details the background of the events that have happened since February 24, 2022, until today, especially the West’s economic sanctions as a response to Russia’s invasion, and highlights the fact that these sanctions, as well as the West’s military and economic aid to Ukraine, have not had the effect on Russia that the West had hoped for.

- Chapter II discusses various indicators related to the Russian economy and concludes that it is in better health than many Western nations, especially in the context of the protracted economic war between Russia and Europe that has been initiated by Europe through the enforcement of Western sanctions on Russia.

- Chapter III talks about Russia’s interconnectedness with the rest of the world and, especially, with Europe, in terms of trade balances, and concludes that Russia is far more important to Europe than Europe is to Russia. It also concludes that an embargo of Russian goods would not fatally harm the Russian economy.

- Chapter IV talks specifically about Europe’s energy dependency on Russia, and shows that Europe’s energy crisis is not one of price but of supply — that the energy supplied by Russia cannot be replaced by any other source; that most European nations are critically dependent on irreplaceable Russian supplies of natural gas, crude and refined petroleum, and coal; that a European energy embargo on Russia will be devastating to European economies and cause the de-industrialization of Europe, while causing minimal and manageable losses to Russia.

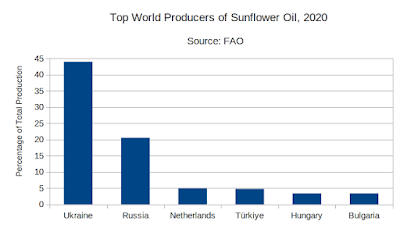

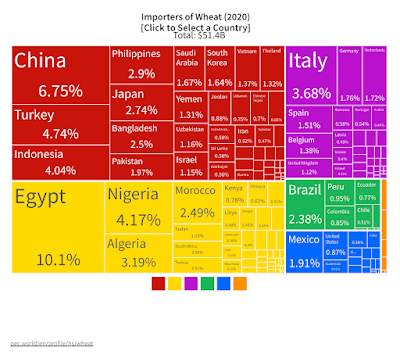

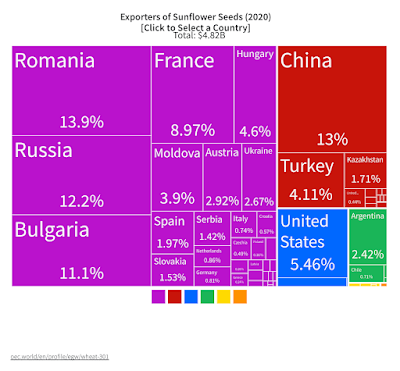

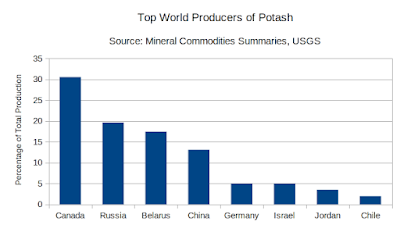

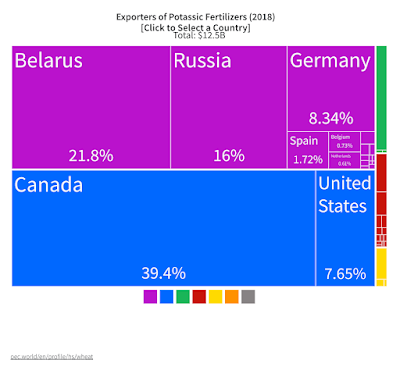

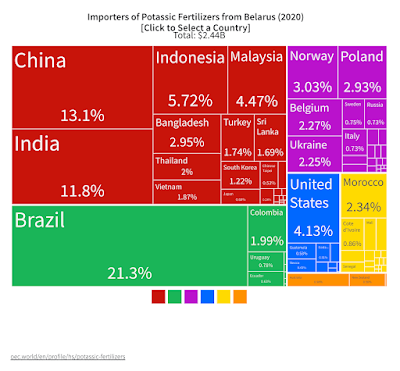

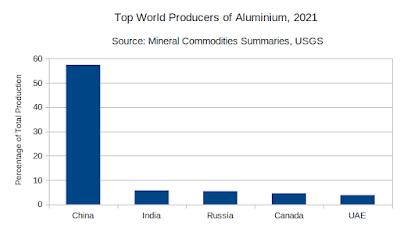

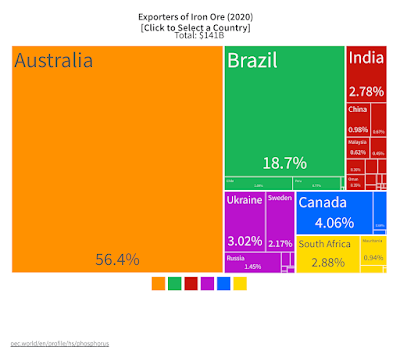

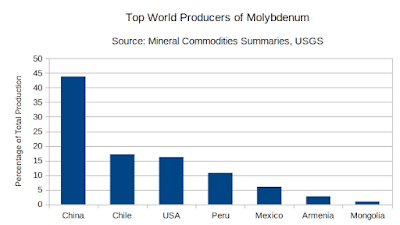

- Chapter V talks about the de-industrialization of Europe which has started to happen because of the West’s sanctions on Russia that have resulted in depriving Europe’s economies, not only of Russian gas, oil, and coal, but potentially of food, fertilizer, and several valuable minerals that Russia is a dominant supplier of, and how this de-industrialization is going to intensify in the coming months and years. It also explains how this crisis is two years in the making, and that the war in Ukraine is just the last nail in Europe’s economic coffin. It also talks about the negative consequences on Europe of the impending oil price cap that it plans to impose on Russian oil exports.

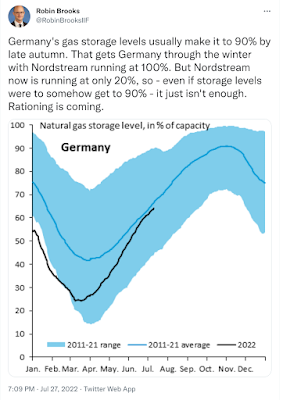

- Chapter VI talks about what Europe can do in response to these challenges, by discussing the most commonly floated solutions: gas storage in Europe, LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas), and renewable energy; and shows how none of these options will be adequate to stave off the coming economic apocalypse for Europe.

- Finally, a SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS chapter talks about the longer-term impact of the West’s sanctions on Russia, and how they will fundamentally change the power calculus in the twenty-first century.

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I: BACKGROUND AND CURRENT STATUS

The Failure of the Economic Blitzkrieg

The Stoppage of Russian Gas and the Nord Stream Sabotage

Who Will Win the Military and Economic Wars?

Those Who Forget History...

A Tale of Ineffective Sanctions

Key Takeaways from Chapter I

CHAPTER II: THE STRENGTH OF THE RUSSIAN ECONOMY

Sanctions are Not New to Russia

Russia’s Economic Parameters: GDP

Russia’s Economic Parameters: Debt-to-GDP Ratio

Russia’s Holdings of US Treasury Bonds

Russia’s Strength in Armaments Production

Key Takeaways from Chapter II

CHAPTER III: RUSSIA’S INTERCONNECTEDNESS WITH THE WORLD

Trade Imbalances and Export/Import Ratios

The Green Transition and the Role of Gas

Destinations of Russian Exports and Origins of Russian Imports

The China-Russia “No Limits” Partnership

A Detailed Look at Some Bilateral Relations

Russia’s Trade Balances with European Nations

Replacing Europe’s Exports to Russia

Key Takeaways from Chapter III

CHAPTER IV. EUROPE’S ENERGY DEPENDENCE ON RUSSIA

Russian Fossil Fuels Do Not Cost Europe Much

Europe’s Energy Needs and Sources

The Global Gas Market and Europe’s Needs

The Global Oil Market and Europe’s Needs

The Global Coal Market and Europe’s Needs

Individual Country Profiles

Germany

Poland

The United Kingdom

Italy

France

Summary of Europe’s Energy Dependencies on Russia

Key Takeaways from Chapter IV

CHAPTER V. THE DE-INDUSTRIALIZATION OF EUROPE

Industry Shutdowns

A Crisis Long Overdue

Natural Gas as a Feedstock

The Impact of the Oil Price Cap

More than Oil and Gas

The Chinese Domination of the Commodity Market

The Infeasibility of Economic Sanctions Against Both Russia and China

Key Takeaways from Chapter V

CHAPTER VI. EUROPE’S ENERGY OPTIONS

Europe’s Gas Storage Tanks

LNG to the Rescue?

Key Takeaways from Chapter VI

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

“Not One Step Backward!”

The Sanity Check that Europe Should Have Done in March

Where Do We Go From Here?

Overall Conclusions

LIST OF FIGURES

CHAPTER I: BACKGROUND AND CURRENT STATUS

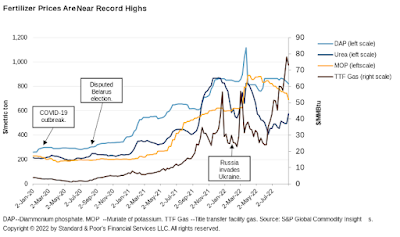

The war in Ukraine is in its tenth month. Europe has reacted in unprecedented ways to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They have imposed several rounds of sanctions designed to choke the Russian economy and bring it to its knees, in order to force it to stop its military operations, in spite of the fact that Europe has been heavily dependent on Russian energy, Russian wheat, Russian fertilizers, and many other commodities originating from Russia.

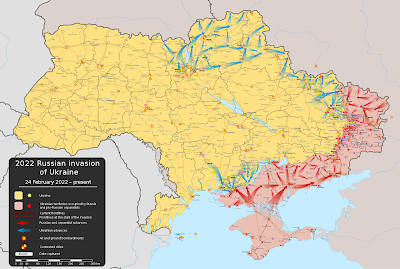

|

| Figure 001. The Russian Invasion of Ukraine |

The Failure of the Economic Blitzkrieg

The initial sanctions from Europe were unprecedented in their severity. The West imposed crippling economic sanctions against Russia, including banning most Russian banks from the SWIFT payment mechanism, which meant that Russia could no longer do business in US dollars. The US seized about half of Russia’s dollar reserves, more than $300 billion worth, that had been deposited in Western banks. The West threatened to sanction any country that was buying oil from Russia. Many prominent Western businesses closed shop in Russia.

The US and Europe believed that these sanctions would be enough to deal a crushing blow to Russia’s war machine and force them to pull back from Ukraine in exchange for the sanctions to be withdrawn. But this did not happen. More than eight months since these “crippling economic sanctions” were imposed, most Russians have barely felt their impact. The lives of ordinary Russians have yet to be impacted in any meaningful way. Yes, McDonald’s has sold its operations to a Russian company, but business for the new company is still going strong. Russians love their burgers under any name.

|

| Fig. 002. The Renamed McDonald's in Moscow |

While oil sales from Russia to the West have dropped, other countries, such as China and India, have ramped up their purchases of Russian oil. Russia has earned record revenues from oil sales ever since the war broke out, even as it gives huge discounts to countries buying its oil.

|

| Fig. 003. Russian Oil Revenues Since the Start of the War |

On the battlefield, Russia today controls 15%-20% of Ukraine’s former territory, and has even formally added parts of territory that once belonged to Ukraine to Russia.

|

| Fig. 004. The Four Provinces Formally Annexed by Russia |

This was not supposed to happen. Russia was not supposed to have the capacity to still wage war after eight months. The Western sanctions policy has failed – at least until now.

|

| Fig. 005. Ganesh Prasad's Representation of Europe's Sanctions Against Russia |

Faced with the failure of their sanctions policy so far, the West (mainly, Europe, the US, Canada, Australia, Japan, and South Korea) had two choices. One, abandon sanctions, pursue negotiations with Moscow, and persuade Ukraine to accept Russian terms to end hostilities; or two, double down, both on economic sanctions and military assistance to Ukraine, in the hope that continued economic sanctions will eventually destroy the Russian economy and continued military aid will eventually swing the war decisively in Ukraine’s favor.

The Stoppage of Russian Gas and the Nord Stream Sabotage

Had the West chosen the first option, the war would have ended, gas supplies from Russia to Europe would have restarted, and possibly the already-ready Nord Stream 2 pipeline would also have started supplying even cheaper energy to Europe in addition to Nord Stream 1, powering Europe’s industry to be world leaders. Of course, this would be seen as a betrayal of Ukraine, after all the bombast involved in European leaders extending their support to the Ukrainians. It would mean a loss of face for European leaders and the ascent of Russia in Europe as the first among equals.

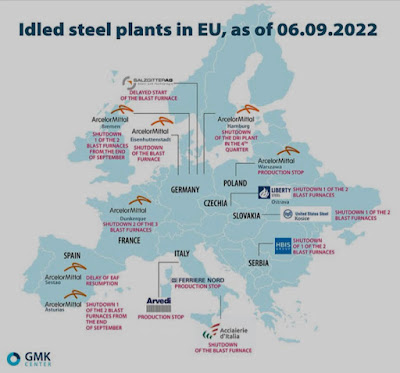

So the West chose the second option, in the hope that eventually, Russia would be defeated. Europe decided that they would wean themselves off Russian gas slowly, and that by December 2022 they would stop importing Russian oil. They “decided,” unilaterally (inasmuch as one can realistically decide such things in a bilateral relationship), that they would continue importing gas from Russia, albeit at reduced volumes, until such time as when they had built enough capacity through alternative means, such as renewable energy. Unfortunately for Europe, it could not control when it would stop using Russian gas. Russia claimed it was having some technical issues that forced it to stop pumping gas to Europe. This caused panic in Europe, with winter more than two months away. In recent times, the entire metallurgy industry in Europe has said that it would be closing down. Some factories have already been shut down, perhaps permanently. Rising energy prices are causing small businesses in the UK and elsewhere in Europe to shut down.

As businesses started closing down all over Europe in response to this development, and just when it seemed like things could not get any worse, an act of sabotage took place that rocked Europe. Both the Nord Stream pipelines were blown up under water and seriously damaged.

Who blew up the pipelines has still not been conclusively established. But it is clear that

- Europe would not have wanted to do so, since it was not happy with Russia’s decision to stop pumping gas. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz was so keen to have Russia start to pump gas through Nord Stream again that he took extra trouble to get the gas turbine that was being serviced in Canada back to Germany to ship to Russia.

- Russia would not be interested in blowing up its own pipeline, because it needed only to turn off the tap if it did not want to supply gas to Europe. Also, having an active pipeline gives Russia great leverage over Europe, because Russia could offer to pump gas to Europe in exchange for sanctions to be lifted. So Russia would not have blown up the pipeline.

- That leaves the US or the UK as the most likely candidates to have blown up the pipelines. The pipelines were blown up in Danish and Swedish territorial waters, and only a US or UK submarine could have entered those waters without causing a general alarm. The US also has the motive to blow up the pipeline. One, the US has been against the Nord Stream pipelines from the very start. Two, the absence of Russian gas means that Europe has no option but to buy expensive American LPG. This would mean a windfall for American oil and gas companies. America prospers, Europe suffers. Further, the UK is not terribly affected by the loss of Nord Stream gas. Continental Europe is.

Europe imports a large percentage of its energy needs. Along with gas, oil is a major import for the European continent. As in the case of gas, Russia has been a major supplier of oil to Europe. Europe has been reluctant to sanction oil because of its huge dependence, but it has been trying to impose a price cap on Russian oil, so that Russia’s revenue from oil sales can be controlled. Russia has said that it will stop supplying to anyone who agrees to the oil price cap. Although the price cap has not been finalized by the West (a unilateral move that Russia has not accepted), many European countries have been voluntarily reducing consumption of oil from Russia. Russia is selling its surplus oil to Asian countries such as China and India. But because the US, UK, and several other Western countries have stopped buying Russian crude, there is a shortage of crude oil and its derivatives, such as diesel and petrol (gasoline), in the Western world. This has had the effect of raising petrol prices in the US, the UK, and Europe. The US has tried to ameliorate the situation in America by releasing almost a million barrels of oil every day from its strategic reserve for the past few months. This has greatly reduced the storage in the American Strategic Petroleum Reserve, and cannot continue for ever. Since the beginning of the war, the level of the strategic petroleum reserve of the US has dropped by nearly a third. Recently, the US tried to influence Saudi Arabia to raise production to compensate for the lack of Russian oil. But the Saudis refused, leading to strong reactions in Washington. So the problem of an oil shortage will last for a long time. Thus, Europe will have to deal with an oil and a gas shortage.

|

| Fig. 006. The Decline in US Strategic Petroleum Reserve Stocks |

Who Will Win the Military and Economic Wars?

At this juncture, it is unclear what the outcome of the military conflict will be. But we can be certain about a few things. The only possible outcomes are that Russia wins the war or that there is a stalemate. Russia cannot be defeated. The reasons for this conclusion are:

- Russia is a far larger economy and a country with a much bigger population.

- Russia is more prosperous than Ukraine and has a bigger industrial base.

- The US and NATO will not directly intervene on Ukraine’s side, even as they might provide military advisors and military equipment.

- China is on Russia’s side.

Let us expand a little on the above points. It was Carl von Clausewitz, the famous military strategist, who said, “War is the mere continuation of policy with other means.” That means that war cannot and should not be seen in isolation — it must be seen as an accompaniment to economics and politics. And therefore, the side that usually prevails in war is the one that is stronger economically and more stable politically.

Ukraine had a GDP of $200 billion in 2021, and Russia had a GDP of $1.78 trillion in the same year — nearly nine times the GDP of Ukraine. Ukraine had a population of 44 million in 2021; Russia had a population of 143 million in the same year. Also, on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis, Russia has a GDP per capita that is more than twice that of Ukraine ($27,970 vs $12,944). All this means that Russia has a higher ability to replace losses in both men and materiel, and a higher ability to endure hardship. This makes it harder for Ukraine to win a war of attrition, which is what this war has now become.

Politically, too, Russia is far more stable than Ukraine. Ukraine is essentially controlled by the US (it was the US that engineered a coup in Ukraine in 2014 and ousted the pro-Russia President, Viktor Yanukovich), whereas Russia is ruled by Vladimir Putin with an iron hand. He has complete control of every aspect of Russia, and has been in power for decades. So Putin not only has the economic resource and a higher population with which to wage war, he also has the authority to demand every resource he needs – such as his calling on reserves to serve in the military, as he recently did. Despite reports in the Western press of unhappiness in Russia at the move, there has been no challenge to Putin’s authority.

The West has made it abundantly clear, and on multiple occasions, that it would simply not consider directly entering the war in Ukraine. This has been clarified both by the US and by NATO. The reason is obvious. Russia is a nuclear-armed state with about 7000 nuclear warheads that are armed and ready, as is the US. The last thing the world needs is the two nuclear superpowers to be directly involved in a confrontation. One misunderstanding, and the whole world will cease to exist.

The last point in the list above, regarding China, deserves amplification. The West in general, and the US in particular, ever since Donald J. Trump’s presidency, have viewed China as an adversary and as their number one global rival. The US has seen China through the lens of a zero-sum game. The US has been actively trying to stop the rise of China, the latest indication of which is the US sanctions announced by President Biden on high-tech semiconductors with regard to China. China, therefore, would not want Ukraine, which is merely a proxy for the US, to prevail over Russia, an ally, in this conflict. And so, in the unlikely scenario where Russia, on its own, appears to be losing this war, China will provide enough support to Russia (both economic and military) to prevent this from happening, because if Russia falls into American control, China will be next. That would mean a repeat of Western domination over China, a repeat of the “century of humiliation” that every Chinese learns about in school, and is determined to prevent, at any cost whatsoever. This is seared into the consciousness of every Chinese citizen. Given that China is a superpower, it will be impossible for the West to defeat Russia as long as China is allied with it – unless, of course, as stated above, the US directly enters the conflict. It is true that if the US and NATO were to get directly enmeshed in this conflict, they could defeat Russia militarily – however, such direct intervention carries with it the risk that a Russia that appears to be losing the war will send a few of its hypersonic nuclear weapons to strike at the US mainland, prompting the US to level Russian cities with nuclear weapons from European NATO sites. This is a worst-case scenario (WWIII), and nobody wants it. If China decides to support Russia more directly than it already has so far, the US and Europe cannot retaliate economically against China because of how deeply China is enmeshed with Western economies and with the Western supply chain (explained in greater detail later in this article). A move to retaliate economically against China will destroy the US and Europe completely, even as it terribly hurts the Chinese economy. And so, if at all it seems likely that Russia will lose, either economically or militarily, China will prevent it from losing.

Those Who Forget History...

It is important to emphasize that China intervening to protect its own national security interest vis-a-vis the United States in a military conflict that does not directly involve it has historical precedent. Communist China has always seen the US as its biggest rival and adversary. China has always refused to countenance the presence of American troops on its borders. In 1950, this is what led to the three-year Korean war between the US and China. The North Koreans invaded South Korea and were on the verge of forcing the Americans out of South Korea. At this juncture, General MacArthur came up with a brilliant plan for an amphibious landing at Inchon to encircle the North Koreans. The plan was successful, and MacArthur was able to beat the North Koreans back to the pre-invasion border — the 38th parallel.

|

| Fig. 007. The Evolution of the Korean War (1950-53) and China's Entry into the War |

But MacArthur was not content with this, and pushed US forces further and further north, until they reached the Yalu river, the border between China and Korea. Mao Zedong had always been clear that he would never tolerate American forces on the Chinese border, and warnings were made diplomatically by China. Unfortunately, these warnings were not heeded by General MacArthur or President Truman.

And therefore, China entered the war in November 1950, sending 300,000 soldiers across the Yalu river and routing the American forces. The Americans had to again retreat south, until MacArthur was replaced by General Matthew Ridgway, who stabilized the front back at the pre-war border, the 38th parallel.

The Korean War cost about 50,000 American lives, but it cost a million Chinese lives. Most of the Chinese troops were lightly armed, with only rifles, as compared to the heavily armed and equipped American troops. But Mao wanted to draw a red line. He had made his point. China would never tolerate America on its borders.

And that is why China will never allow Russia to be defeated militarily or become a Western puppet through a coup. We cannot forget that Russia is actually a buffer state (albeit a giant buffer state) between Europe and China. If the US manages to install a puppet in Moscow, that means that NATO weapons can potentially be stationed on the vast Russia-China border, presenting an existential threat to China. This would be a serious threat to Chinese sovereignty. Thus, the Chinese will do whatever it takes to stop a Western victory in Ukraine. This is why none of the current battlefield reverses (as widely reported in the Western press), such as the Ukrainian takeover of Kherson, really matter. If push comes to shove, the Chinese will throw their considerable weight behind Putin to ensure that Putin does not lose. They simply cannot afford to have an unfriendly government in Russia. They will absorb whatever economic consequences that follow from such a decision, because this is an existential issue.

We must therefore only consider the situations where Ukraine a) either loses this war or b) continues to hang on grimly in a stalemate situation, perhaps even for years, if at all it can hold out for that long. If Ukraine loses this war quickly, there is a possibility that Europe breaks free of America’s influence and quickly mends fences with Russia. In such a scenario, Europe might escape relatively unscathed.

But if this war rages on inconclusively for an extended period (and, in this context, even a war that lasts several more months could be thought of as “extended”), Europe will be utterly destroyed economically. This is the most likely scenario at the current time, as European countries, most perplexingly, have actually hardened their stance despite eight months of a failed combination of economic sanctions against Russia and military aid to Ukraine.

The reason why Europe will be destroyed if this war continues is their extensive dependence on Russia and China. I have so far only alluded to oil and gas, but Europe is so dependent on these two countries that it simply cannot survive with a policy that is hostile to either of these countries. Currently, many major European countries, such as France and Germany, are openly hostile to both countries. This will result in their total economic destruction, unless they reverse course fairly soon.

A Tale of Ineffective Sanctions

Russia is a nation with huge natural resources, and is therefore indispensable to the global economy. Despite this reality, since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the West has imposed several rounds of unprecedented economic sanctions on Russia. The stated aim of these sanctions has been “to reduce Putin’s ability to wage war.” Are these sanctions likely to have the intended effect? Let us analyze this.

The main thrusts of the sanctions were along the following directions:

- Western governments seized Russian assets without compensation, such as Russian government assets in Western banks. This is little short of outright theft, and amounted to the seizure of about $400 billion of Russian Central Bank reserves. In addition, assets of influential and wealthy Russian citizens, such as yachts of Russian oligarchs, were also illegally seized by Western governments without compensation. The freezing of the Russian Central Bank reserves was considered by most economists to be an unprecedented measure, almost like a “nuclear option” on the Russian economy. Most Western leaders expected the Russian economy to collapse overnight due to hyperinflation. But the Russian economy recovered after a brief period of high inflation, when the ruble temporarily sharply lost value. But now the ruble is trading at levels which are higher than its levels were before the war began.

- The US and Canada banned the import of Russian oil, gas, and coal. Many other countries voluntarily chose to not import Russian fossil fuels.

- Western countries voted to ban Russia from using the SWIFT payment mechanism. Essentially, this meant that any country that used SWIFT to transfer money to Russia could no longer do so, and that Russia could no longer use SWIFT to transfer money to any other country. The SWIFT ban affected not only trade between the West and Russia, but between any other country, such as India or China, with Russia, because it made it impossible for these countries to pay Russia in dollars for their gas or coal or oil. Russia anyway could not buy anything with these dollars, because most Western markets had been closed to them when SWIFT was made unavailable to Russia. They could not pay India or China or the UAE with dollars to buy goods from them because they had been locked out of SWIFT.

- Some countries banned specific technologies and products. South Korea banned the export of semiconductors, IT equipment, sensors, lasers, maritime equipment, and aerospace equipment, something that was also done by the USA. The EU banned the export of aircraft spare parts to Russia.

- Many companies stopped their operations within Russia – for example, McDonald’s closed down their operations in Russia and sold them to a Russian firm; BP exited its joint venture with Rosneft, in which it had invested $25 billion; and Shell also exited its Russian ventures. Many of these moves were forced, because these companies could no longer do business in Russia without violating Western sanctions against Russia.

- Germany suspended the opening of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline just when construction was complete.

- Western governments sanctioned specific individuals, such as Russian President Vladimir Putin, Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, and more than 300 members of the Russian Parliament, the Duma.

- Europe has pondered stopping the buying of Russian fossil fuels on numerous occasions, but has been stopped by practical considerations every time. For instance, on 8 March, 2022, the EU proposed reducing gas purchases from Russia by up to two-thirds by the end of 2022, and completely phasing it out by 2030. On 18 May, 2022, the EU presented an updated plan to completely end reliance on Russian oil, gas, and coal by 2027. Neither of these plans ever got complete agreement, and so were never implemented. A key reason, as we shall see later, is that some countries in Europe are extremely dependent on Russian energy, whereas others are not. On 2 September, 2022, the EU proposed to cap the price of Russian oil so that Russia could not profit from oil sales. In response, Russia said that it would not sell oil to any countries that sought to impose a price cap on it. The price cap would be enforced by denying shipping insurance (by Lloyd’s of London, the leading insurer of maritime shipping) to any vessel that was not complying with the price cap. The price cap on Russian oil was finally agreed to by all EU countries on October 6, 2022, with the price to be finalized on December 5, 2022.

- Australia banned the export of alumina, bauxite, and other aluminum ores to Russia.

- Many countries closed their airspace to Russia, inviting retaliatory closures to their aircraft by Russia.

This is not a comprehensive list, but probably lists the most significant steps. I am not covering the truly silly moves, such as refusing to teach Dostoyevsky in Universities and not allowing Russian sportspersons to participate in competitions. But even many of the measures described above are not that far removed from such silliness. For instance, seizing the yachts of billionaire Russians is highly unlikely to make Putin want to stop his invasion. It is just Western governments being petty. Similarly, sanctioning Putin or Lavrov or members of the Duma has little more than symbolic value. And closing your country’s airspace to Russia is a stupid idea, because when Russia retaliates, it is you who are going to have a much harder time, given how big Russia is.

Incidentally, as the map below shows (created by Artemis Dread, CC BY-SA 4.0

|

| Fig. 008. How Sanctions Against Russia are a Western Enterprise |

So, keeping that in mind, let us understand what the material and significant aspects of Western sanctions are, before moving on to understand if they can be effective in realizing their aim.

Clearly, freezing half of Russia’s foreign exchange reserves was a major blow to the Russians. But then, by banning Russia from SWIFT, the West escalated things further and made all of Russia’s foreign exchange irrelevant, because they could not use all that money to buy anything.

The banning of Russia from SWIFT was supposed to be the West’s masterstroke. Everyone in the West truly believed that it would bring Russia to its knees. If anything could have crippled the Russian economy, this was it. And indeed, for a short while, these sanctions appeared to have had their effect. Overnight, the ruble crashed and, from a pre-war level of about 79 rubles to the dollar, it fell to nearly 139 rubles to the dollar, before the Russian central bank acted decisively and stopped the rout. Since then, by placing export controls on the ruble and by insisting on payment for gas in rubles, Russia managed to get the ruble back up, and today it trades at a higher level (around 62 rubles to the dollar) than it did before the war. Of course, this level is not terribly useful, because not many rubles are being exchanged for dollars or euros, because nobody in the West is even allowed to trade with Russia, except for the gas and oil sales. But there has been no run on the Russian banks, and the Russian financial system survived the West’s “nuclear strike.”

|

| Fig. 009. The Fall and Rise of the Ruble After the Invasion of Ukraine, 2022 |

Since then, the Russians have been making money hand over fist, because the price of crude oil and natural gas shot through the roof in Europe. Since Europe was still highly dependent on Russia for natural gas, oil, and coal, some Russian banks were still allowed to use the SWIFT system. Europe was therefore unable to completely stop financing Russia’s war on Ukraine, and in fact Russia made far more money in six months than they normally would make in a year. It is to plug this loophole that Europe is now thinking of placing a price cap on Russian oil. But Russia knows that it has the winning hand here. There is no reason for Russia to agree to any cap on its price, and Putin has clearly told Europe that if any country tries to impose a price cap, he will simply stop selling to that country.

The West seems to be gambling on the idea that Russia needs Europe’s money so badly that they will eventually be forced to agree to the price cap. There doesn’t appear to be any “Plan B” in case Putin refuses to comply with the price cap.

Some of the other sanctions, such as denying Russia high-tech equipment and semiconductors, might eventually hurt Russia, but these are higher-level concerns, and so they will take a long time to start biting. Energy to heat the home and power industry is a far more basic concern. Russia can live without advanced semiconductors; but can Europe live without gas and oil to heat their homes in the winter and to power their industry and cars?

So, what we need to understand is:

- How strong is the Russian economy? How badly will Russia be hurt if Europe, the US, Japan, Korea, Canada, and Australia refuse to buy its fossil fuels? In other words, what is the economic impact of a Western ban on Russian fossil fuels?

- How strong are European economies? How badly will European countries be hurt if they do not have access to Russian fossil energy?

- What other economic levers (other than fossil fuels) exist that can influence the outcome of this economic war?

- What is going to be the effect of all this on the economies of Europe?

- Are there any solutions that can help Europe avoid the worst consequences (such as moving from pipeline gas to LNG, or using renewable energy?)

Indeed, we can turn Clausewitz’s famous words around, because the converse is also true: Economic war is merely the continuation of political and military war with other means. So the West is using economic war against Russia in preference to sending their soldiers to die. They are happy to export weapons to Ukraine and let them do the fighting, but they want to defeat Russia “with other means” — in this case, economic means.

In the next two chapters, we will see if this is possible, and will try to answer the questions posed above.

Key Takeaways from Chapter I

-

The West imposed unprecedented sanctions on Russia after the start of the war

- These sanctions have failed to crush the Russian economy or stop their war effort

- Despite the sanctions, Russia has made huge profits on the sale of oil and gas because of skyrocketing prices

- Russia continues to sell oil and gas to India and China

- The non-Western world did not join in the sanctions

- While the value of the Ruble temporarily dropped, it quickly recovered

- The West has been incrementally adding more sanctions, with little to show for them

- Russia today controls 15-20% of the former territory of Ukraine

-

The Nord Stream pipelines were sabotaged

- They are now unusable and will not be usable for a long time

- Based on motives, the US is the prime suspect behind the sabotage

- The US and NATO have repeatedly ruled out getting directly involved in the war

- China will not let Russia lose either the military or the economic war

- The West is going to try to impose an oil price cap on Russia

- Russia has said that it will stop selling oil to countries that participate in the cap

CHAPTER II: THE STRENGTH OF THE RUSSIAN ECONOMY

Sanctions are Not New to Russia

One of the things that is often missed by Western commentators is the fact that sanctions are not new to Russia. Russia has been sanctioned ever since 2014, when they invaded and annexed the Crimea in response to the US-backed coup in Ukraine that ousted the democratically-elected President Viktor Yanukovich and installed the hand-picked American puppet, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, as President. Yatsenyuk was later succeeded by Petro Poroshenko as President and then by Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who is the curent President. Starting in 2014, the West imposed several rounds of sanctions on Russia. The initial sanctions only consisted of travel bans and some asset seizures against specific individuals. But the Third Round of sanctions, applied on 17 July 2014 by the US, had some wide-ranging measures. This included an embargo on sales of arms and arms-related materials to Russia, a ban on sales of dual-use (civilian/military uses) materials, and a ban on export of equipment related to the oil industry in Russia. The measures also had restrictions on buying of long-term bonds by Russia. In the following months, many European countries followed suit with similar measures, including restrictions on the ability of Russian businesses to obtain medium and long-term loans from European banks. On 11 September 2014, the US imposed restrictions on the Russian oil industry, specifically preventing them from accessing US technology related to oil exploration and banning the sharing of technology between American oil companies and Russian oil companies such as Rosneft, Gazprom, and Lukoil. The US also imposed restrictions on Russia’s largest bank, Sberbank, and a large arms manufacturer, Rostec, limiting their ability to access the US debt markets. On 3 October, 2014, then-US Vice President Joe Biden claimed that the US actions had been hugely successful, when he said, “And the results have been massive capital flight from Russia, a virtual freeze on foreign direct investment, a ruble at an all-time low against the dollar, and the Russian economy teetering on the brink of recession.” VP Biden claimed this even though the ruble had only gone down from around 35 rubles to a dollar to around 40 rubles a dollar. Western sanctions did hit Russia badly, but eventually the ship righted itself: the ruble would eventually go down to as much as 82 rubles to the dollar before eventually settling down to a stable level of about 60 rubles to the dollar in late 2014, which is where the ruble is today in 2022, after the West’s best efforts. Despite Biden’s grandiose claims of “massive capital flight” and the Russian economy “teetering on the brink of recession,” Russia seems to have done quite allright. Biden has clearly not lost his penchant for hyperbole in the last eight years for, after the “nuclear” sanctions imposed by the West in February 2022, whereby Russia’s foreign currency assets were seized and it was barred from SWIFT, he again gloated, in response to the temporary crash in the value of the ruble, saying “the ruble is now rubble.” Of course, rumors of the death of the Russian economy turned out to be vastly exaggerated.

|

| Fig. 010. How Western Sanctions Affected Russia in 2014 |

So Russia has been subject to sanctions since 2014, and especially on sanctions related to weapons and weapons-related technology. They have had eight years of adjusting to a new way of doing things, of being more self-reliant in terms of technology and defense equipment. This is why the claims of American media commentators that the current sanctions have forced Russians to ransack their washing machines for microprocessors to use in their weapons are ludicrous.

Russia’s Economic Parameters: GDP

While the current (post-February 24, 2022) sanctions on Russia are rightly described as unprecedented, the sanctions of the previous eight years were pretty rough on Russia as well. Let us see how Russia coped under those sanctions, to understand the resilience of the Russian economy and industrial base.

Russia has a fairly advanced manufacturing and engineering base and, in fact, has been spending more on manufacturing as a share of GDP than most European countries over the past decade, with the exception of Germany. Manufacturing constitutes close to 13% of Russia's GDP, as compared with France, Great Britain, and the US, where it contitutes in the range of 9-11% of GDP. So, the idea that Russia is a weak and backward country is ludicrous.

|

| Fig. 011. Manufacturing as % of GDP, Russia v/s Europe and USA |

That Russia has weathered the sanctions storm it has faced since 2014 rather well is also seen in a comparison of average annual GDP growth rates of Russian and major world economies since 2000, when Vladimir Putin assumed control of Russia. Despite the 2007-8 financial crisis, the US-China trade war of 2018, and various other issues, Russia has clearly outperformed Europe, the UK, and the US.

|

| Fig. 012. Avg. GDP Growth Rate, 2000-2019, Russia v/s Europe and USA |

You cannot survive eight years of tough sanctions and have a prosperous economy unless you have made adjustments to account for the fact that you will not be able to import many essential products. Despite the ban on weapons technology and dual-use items that has been in force since 2014, Russia still has a viable arms industry. So, to imagine that they will suddenly collapse under the weight of the newer sanctions is delusional.

|

| Fig. 013. Annual % GDP Growth Rate, 2000-2018, Russia, UK, Germany |

Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has slowly become economically stronger, although it is still a developing country, as its GDP per capita, indexed to purchasing power parity (PPP), shows. While it still has a way to go in catching up to the level of a developed country like the US or a Western European country like France or Germany, the GDP per capita, PPP, has increased by a compounded annual growth rate of more than 3% in the last 20 years under Vladimir Putin (from $14,570 to $29,970, in constant 2017 USD), as the two graphs below show. While Ukraine, too, has grown robustly in these 20 years, the absolute level of Ukraine’s GDP per capita (PPP) is less than half of Russia’s, at $12,944. This is one more reason why we cannot expect Ukraine to hold out too long against Russia.

|

| Fig. 014. GDP Per Capita, PPP, 2000-2021 |

|

| Fig. 015. Average % annual growth, GDP per capita, PPP, 2000-2021 |

Russia’s Economic Parameters: Debt-to-GDP Ratio

Another indicator of Russian self-reliance is the total debt-to-GDP ratio, which is the lowest among all the countries in this cohort, by far, close to 20%. This shows how responsibly Russia has managed to develop its economy and industry. Having a low debt-to-GDP ratio means that you are more self-sufficient and independent than other countries. The US is highly indebted (debt around 100% of GDP in 2018, but around 135% today), but is not unduly bothered by this, because it holds the reserve currency, the US dollar. So, whenever a financial crisis hits the country, it prints more paper money, as it started doing since the Global Financial Crisis in 2007, which was caused by inadequate regulation of the US housing market. Since the US dollar is the world reserve currency, other countries invest their surpluses buying US Treasury bonds as a safe investment, and run up huge deposits of US treasuries. Both China and Japan have huge holdings of US Treasury bonds. That’s one reason why Japan’s debt is 200% of its GDP. Other European countries are also highly indebted – the UK’s debt was around 160% of GDP in 2018, and France’s and Spain’s debt were both around 100% of GDP in 2018.

|

| Fig. 016. Total Debt as a Percentage of GDP, for Russia and Various Advanced Countries |

|

| Fig. 017. The Rise in China and Japan's Ownership of US Treasury Bonds |

The World Bank has done a detailed study of the impact of high debt on the economic health of a country, and has come up with a “tipping point” of 77% for the debt-to-GDP ratio, up to which it is safe to have national debt, and after which the annual GDP growth rate takes a hit of 0.017% for every percentage point that the debt is higher than 77%. Thus, if the national debt is 136% of GDP (and hence 59% above 77%), the reduction in annual GDP growth rate will be 0.017x59 = 1%. Keep in mind that this will be compounded for every year that the national debt is higher than 77%.

Based on this formula, the annual reduction in GDP growth rate caused by the high debt in several countries can be calculated each year. I have done this, and the results can be seen in the next graph.

|

| Fig. 018. Annual GDP Growth Rate Due to High Debt |

The results are striking. Japan, with a very high level of indebtedness, is losing nearly 2 percentage points of GDP growth each year currently due to its high national debt. The United Kingdom is losing nearly 1.5% of GDP growth each year because of high levels of debt. France, the US, and Spain are all losing nearly 0.5% of GDP growth currently because of high debt.

What is also noticeable is that levels of indebtedness rose dramatically after the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-08, as countries started borrowing to get out of the crisis, powered by the paper dollars of the US and by buying US Treasury bonds. This is only a band-aid approach, and does not address the root cause of the crisis, which was lax regulation leading to criminal malfeasance. The US continued the practice of printing money, also known as “Quantitaive Easing” (QE) for four years, finally stopping it in 2012, after accumulating $4.5 trillion of new assets. When the Covid pandemic hit, the US again resorted to QE in March 2020 to provide relief to Americans. The results of this reckless policy are now becoming evident with skyrocketing inflation in Western countries over the last year. As the old American saying goes, “There is no such thing as a free lunch.” By printing money since 2007, the United States simply kicked the can down the road. But you cannot keep kicking the can endlessly. At some point, you have to pay for it. That point, coincidentally, happened to be almost the same point as the time when Vladimir Putin started his “special military operation” against Ukraine: Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022; the US Federal Reserve ended Quantitative Easing on March 10, 2022. The US chose the worst possible time for a confrontation with Russia – at a time when its treasury was artificially puffed up. This is because all debt eventually needs interest payments – this is called debt servicing. As long as you are printing more money, it is easy to pay the interest (debt service) on your existing debt. But once you stop the QE, you have to start paying the interest on the debt you owe, and you are not printing any more money. This is the reason for the high inflation in the US.

It is possible to look at the long-term compounded effects of this annual reduction to the GDP growth rate (because of high indebtedness) on the projected GDP after a number of years. I have done this calculation by using elementary compound interest calculation based on yearly compounding, and the results can be seen below in the charts for Japan, Great Britain, and the USA, three countries with high levels of indebtedness.

|

| Fig. 019. Compounded GDP Growth Factor with Year 2000 as Base, Japan and UK |

|

| Fig. 020. Compounded GDP Growth Factor with Year 2000 as Base, USA |

Let me explain what these charts mean. The “Id” curve (for “Ideal”) is the value of one dollar of GDP (at the beginning of the year 2000) at the end of any year, based on the reported annual GDP growth rates from 2000 to 2018, by doing annual compound interest calculation. The “Act” curve (for “Actual”) is the value of one dollar of GDP (at the beginning of the year 2000) at the end of any year, but by using the corrected annual GDP growth rates (= reported GDP growth rate – hit on GDP growth rate by using the World Bank formula), again by doing annual compound interest calculation. The point corresponding to each year on the x-axis is the value of the dollar at the end of the year. That is why the value for the year 2000 is higher than 1, because the GDP has grown.

So, what we can infer from these charts is that since the GDP for the USA in the year 2000 was $13.75 trillion (constant 2015 US dollars), the projected value at the end of 2018 based on the reported GDP growth rates would be 1.47 times the 2000 value, but the actual value at the end of 2018, based on the corrected GDP growth rates would be 1.44 times. This may not seem like a big deal at first, but given that they multiply a very large number, the difference is substantial: $413 billion. This is the amount that the USA has lost by having such a large public debt. For reference, the actual ratio of the GDP values for the United States for 2019 and 2000 is 1.45 (which is not surprising, because I have used a simple model of annualized compound interest above, and so one would not expect an exact match.)

The differences for the UK and Japan are much worse. The projected value of $1 of GDP at the start of 2000 for the UK would be $1.41 at the beginning of 2019 based on the reported growth rates and $1.24 at the corrected GDP growth rates. That is a difference of $0.17 per dollar. In absolute terms, that amounts to $393 billion, which is a significant amount for the UK. For Japan, the values are $1.18 and $0.92 (in fact, the model suggests that the Japanese economy is contracting since 2010 because of its huge debt to the USA, because the projected value of $1 is less than $1 from that year onwards), which amounts to $1037 billion, or $1.037 trillion of GDP loss at the beginning of 2019.

Countries which are already highly indebted are not in the best position to get into an extended physical or economic war. Their economies cannot take further blows. The US and European economies are already highly indebted. War (whether military or economic) is a very expensive proposition. The West came out of the Global Financial Crisis not too long ago (2008) and then endured a horrific slowdown because of Covid-19 in 2019-20. Western economies are very fragile, and Western leaders should have thought a thousand times before deciding that military confrontation with Russia was worth it. They appear to have suffered from delusions of overconfidence. What has added to US national debt is the huge spending on the military caused by the 20-year wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, each of which is estimated to have cost America $2 trillion, with the total bill of the American "War on Terror" estimated at $8 trillion.

With such low levels of indebtedness (a debt-to-GDP ratio of less than 20%), Russia is better positioned to survive both a physical as well as an economic war, as well as any economic blockade by the West.

Russia’s Holdings of US Treasury Bonds

It is because of these reasons, and because of the implications of high levels of US Treasury bonds on its national interests, that China began divesting its US Treasury bonds, starting in 2017, when Donald Trump made it America’s enemy number one and started a trade war against China. China realized the danger of having so much of its wealth locked up in US financial instruments. At the time, the US had not yet demonstrated its will to use its Treasury Bonds as a financial weapon yet. But they finally did it when Russia invaded Ukraine, when they froze Russian reserves held in the US. China was worried about it when tensions began to soar with the US under Trump, and the US’ actions with respect to Russia have only confirmed their suspicion. And that is why, since 2017, China has been steadily selling off its holdings of US Treasury bonds. The chart below only shows the values until January 2022, but holdings have continued to drop, and in August 2022, they had gone down to $970 billion from a peak of more than $1.2 trillion. That is a drop of more than 25% in five years. China has been doing this slowly and gradually, because a sharp sell-off would mean a drop in the value and cause them a loss. But it is clearly a carefully coordinated strategy.

|

| Fig. 021. Reduction in China's Ownership of US Treasury Bonds |

Russia had already faced hostile sanctions from the US, and so it began preparing for America’s economic war well in advance. In the period between October 2017 and May 2018, Russian holdings of US treasury bonds fell from more than $100 billion to less than $15 billion as they sold off most of their holdings.

|

| Fig. 022. Drop in Russia's Ownership of US Treasury Bonds in 2017-18 |

More recently, between 2000-2022, Russia sold off even more of its holdings of US Treasury bonds, from $12.5 billion to just $2 billion. This was very useful to them when the US decided to freeze Russian assets after the start of the war.

|

| Fig. 023. Recent Drop in Russian Ownership of US Treasury Bonds |

So, if Russia was reducing its dependence on the US dollar for its reserves, where was it storing its wealth? The answer: Gold. Russian stockpiles of gold have skyrocketed in recent years. From less than 500 tons of gold in 2000, Russia today has a stockpile of more than 2,200 tons. Russia started dumping dollars and buying gold after the financial crisis of 2007-08, a sign that Russia (along with much of the rest of the world) had begun to lose confidence in the West’s financial system. Their purchases and stockpiling (Russia is also one of the top producers of gold in the world) of gold helped their reserves grow by five-fold in the last 20 years. In value terms, Russia’s gold reserves increased from less than $5 billion in 2000 to more than $130 billion by 2022. All this was done to protect Russia against hostile economic moves by the US.

|

| Fig. 024. Growth in Russian Gold Reserves in Million USD |

|

| Fig. 025. Growth in Russian Gold Reserves in Tons of Gold |

The rest of the world had reposed their trust in the US by depositing their excess funds in US treasuries. But once the US showed a willingness to weaponize this dependence of other countries by trying to blackmail them, as they have now done with Russia, the rest of the world does not feel their money is safe with the US. As many commentators have reported, there is now a move to “de-dollarize” the world – to do business in currencies other than the dollar and the Euro, and instead move to other currencies such as the yuan, and to use payment mechanisms other than SWIFT, such as the Russian SPFS and the Chinese CIPS.

Russia’s Strength in Armaments Production

Russia has also traditionally had a strong arms industry, second only to the US. Until 2012, the production of arms by the US and Russia was comparable. Since then, there has been a decline, but Russia is still the second-largest arms producer in the world. An indication of this can be seen by looking at the following chart, which shows the top 4 arms exporters in the world. This is obtained from the website of the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). The values on the y-axis deserve explanation. SIPRI likes to show arms exports not by financial values of exports (because these can vary with supply and demand, and so may not reflect the inherent value of the weapons traded), but by the production cost, which they call Trend Indicator Value. As they explain their methodology on their website,

SIPRI statistical data on arms transfers relates to actual deliveries of major conventional weapons. To permit comparison between the data on such deliveries of different weapons and to identify general trends, SIPRI has developed a unique system to measure the volume of international transfers of major conventional weapons using a common unit, the trend-indicator value (TIV).

The TIV is based on the known unit production costs of a core set of weapons and is intended to represent the transfer of military resources rather than the financial value of the transfer. Weapons for which a production cost is not known are compared with core weapons based on: size and performance characteristics (weight, speed, range and payload); type of electronics, loading or unloading arrangements, engine, tracks or wheels, armament and materials; and the year in which the weapon was produced. A weapon that has been in service in another armed force is given a value 40 per cent of that of a new weapon. A used weapon that has been significantly refurbished or modified by the supplier before delivery is given a value of 66 per cent of that of a new weapon.

|

| Fig. 026. World's Largest Arms Exporters, 2000-2020 |

Russia’s arms manufacturing capability is another measure of its self-reliance. Unlike most other countries, it does not need to depend on other countries for weapons. Given that it is one of the leading global arms exporters, making weapons for itself, such as aircraft, tanks, and missiles, should not be difficult. This is another reason why sanctions will not hurt Russia’s ability to continue this war. It should be noted that Russia’s arms industry has been under sanctions since 2014, and still has not collapsed, managing to develop and sell several world-leading weapons, so it is fair to say that Russia’s armaments industry has found ways to survive Western sanctions. Ukraine, on the other hand, is highly dependent on the West for its weapons.

In 2021, the US Congress authorized a study to determine the threat to the US from the Russian Defence Industry. Its report (Congressional Research Service report R46937) was released in October 2021. Among the things the report concluded were (quotes from the report):

- Russia’s defense industry is capable of producing advanced systems across most weapons categories.

- Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine and the imposition of Western sanctions reinforced an existing tendency of self-sufficiency, with Russia’s defense industry attempting to become even more self-reliant.

- In 2011, Russia launched a 10-year armament program, known as GPV-2020, with a goal to modernize the military’s weaponry. According to external analysis, the program funding allowed the sector to recapitalize many of its stagnant sectors, import precision tools, recruit a high-quality workforce, increase production, and resume development of R&D programs that had been on hold since the 1990s. According to Russian officials, the defense industry has largely achieved the goals of GPV-2020 and developed capabilities to produce systems across all major weapons categories.

- Russia asserts it has increased its ability to serially produce upgraded systems, increase production volumes, and innovate new designs (such as hypersonic and cruise missiles, electronic warfare, and air defense systems). Analysts generally consider such new systems to be formidable, increasing Russia’s military capability and competitiveness in foreign arms sales.

And so, even as Western media reports since the start of the 2022 Ukraine war suggest that the Russian military is poorly equipped, and that Russian military equipment is outdated relative to that of NATO, the US government clearly knows better. It knows that it is dealing with a state-of-the-art military machine. As CRS R46937 says, Russia’s defence industry has been becoming more and more self-reliant since sanctions were imposed on it after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. This is why it is hard to imagine that the new sanctions imposed in February 2022 will considerably impact Russia’s ability to produce aircraft, tanks, and weapons to continue to prosecute the war. As CRS R46937 notes,

The Russian government and senior government officials have directed an extensive import substitution program to shift the defense industry toward a reliance on domestically produced components. Import substitution could reduce the defense industry’s exposure to foreign sanctions, improve the purchasing power of domestic military expenditure, and increase profit from foreign arms sales. This policy has become more important now that European and U.S. sanctions have limited Russian access from key suppliers and Ukraine has severed access to its defense industry. Russia’s import substitution program has been somewhat successful in replacing Western components and developing domestic manufacturing and production expertise; before 2014, Russia relied on Western producers for dual-use goods, especially high-end technology.

The report also points out that Russia has successfully been able to shake off its reliance on the Ukrainian defense industry:

Russia’s defense industry has been increasingly successful in reducing its reliance on systems and components produced in Ukraine before 2014. Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Ukrainian defense industry provided materiel such as helicopter engines, transport aircraft, rockets and missiles, and gas turbine engines and power components for naval vessels. The loss of Ukrainian engines affected Russia’s shipbuilding, with delays and cancellations of ships under construction. For example, the loss of Ukrainian producers appears to have led Russia to sell Project 11356 frigates to India and to have contributed to delays in the production of Project 22350 Admiral Gorshkov class frigates. Russia has begun to replace imported diesel/gas turbine engines with domestically produced ones.

The US Congressional Research Report also explains why several countries, such as India, cannot abandon or sanction Russia — their defense requirements and weapons inventories are too closely tied to Russia. The report uses data from SIPRI to give the value of arms exports from Russia to several key countries. Below are figures from the report showing Russian arms exports to different countries, using Trend Indicator Values to measure exports.

|

| Fig. 027. Russian Arms Exports to Algeria, 1991-2020 |

|

| Fig. 028. Russian Arms Exports to China, 1991-2020 |

|

| Fig. 029. Russian Arms Exports to Egypt, 1991-2020 |

|

| Fig. 030. Russian Arms Exports to India, 1991-2020 |

Key Takeaways from Chapter II

- Russia has lived with sanctions since 2014

-

Russia’s economy has grown well even under these sanctions

- Its average GDP growth rate is better than all Western countries

- Average GDP growth rate, per capita, PPP, is better than all Western countries

- Manufacturing is robust at 13% of GDP

-

Russia has a very low debt-to-GDP ratio (20%)

- This makes it very independent

- Russia is capable of absorbing economic shocks

- The West, with much higher debt-to-GDP ratios (of the order of 100% or more) cannot handle more shocks

-

Russia has been making itself independent of the West

- By divesting itself of US Treasury bonds

- By reducing its US dollar holdings

- By investing its wealth in gold

-

By forging a global partnership to de-dollarize

- Other countries like China have also reduced their US Treasury holdings

-

Russia is a major arms manufacturer and exporter

- Technologically independent of the West

- Has a greater ability to continue war than Ukraine

- Modern and competitive with the West, according to US assessment

- Shown an ability to survive severe Western sanctions since 2014

CHAPTER III: RUSSIA’S INTERCONNECTEDNESS WITH THE WORLD

Normal trade embargoes work well if you can choke another country which is in desperate need of something and cannot get it because of your embargo. A prime example of this is the Pacific War in the Second World War, which was triggered because the US imposed a trade embargo on Japan because of its invasion of China in 1933. Japan had a vision of imperial conquest of Asia, which was unacceptable to Great Britain and the USA, because it conflicted with the imperial visions of these two empires. Japan needed raw materials even to sustain its empire in Manchuria. The American embargo was preventing the Japanese from buying vital raw materials to sustain its ambitions. The only way to break the embargo was prosecute war against the US and Great Britain. Japan’s immediate problem was Great Britain, because they could get most of their raw materials from East Asia, specifically Malaya and the Dutch East Indies (modern Malaysia and Indonesia). But they were worried about the naval power of the US and knew they had to knock them out. The result of that calculation was the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Unfortunately for the Japanese and fortunately for the rest of the world, their calculations went wrong, and they could not hit the American aircraft carriers at Pearl Harbor because those had previously sailed out and therefore escaped the carnage of the surprise attack. This left the Americans with enough naval strength to defeat the Japanese on the high seas.

But the current situation involving Russia is an embargo in reverse. The West does not want to deny Russia goods. They want to deny them income. The embargo on Japan was fairly easy, because Japan wanted to import iron ore, coal, rubber, tin, zinc, and a host of other materials that their small island could not produce. Russia, on the other hand, produces gigantic quantities of commodities. They need markets for their commodities. The West believes that by not allowing Russia to sell these commodities, they can starve Russia of the income it would derive from selling these commodities. The US had earlier done this with Iraq after the 1991 Gulf War, where it refused to allow Iraq to sell its oil; and it has imposed similar sanctions on Iranian oil today. But while the sanctions on Iran have caused hardship, decades of sanctions against the Islamic regime in Iran have not succeeded in removing them from power or seriously eroded their support among the people. (It is true that there is currently some unrest in Iran, but it is unrelated to the US sanctions.)

The question then becomes: who needs whom more? Does Russia need the income from selling commodities more than the West needs the commodities themselves?

There are two sub-questions here:

- Can a complete embargo on Russian sales of its commodities be imposed?

- If a complete Western embargo could be imposed on Russia’s energy sales, could Russia survive?

Trade Imbalances and Export/Import Ratios

To understand this, we need to understand a concept known as the trade imbalance. The trade balance of a country (also known as the Balance of Trade, or BoT) is defined as the value of its exported goods and services minus the value of its imported goods and services. If the value of the exports exceeds the value of the imports, the country is said to have a trade surplus. If the value of the imports exceeds the value of the exports, the country is said to have a trade deficit. These quantities can be defined for a country as a whole (with respect to the rest of the world) or for a country with respect to a region (for instance, for Russia with respect to Asia) or for a pair of countries (for instance, for Russia with respect to Germany).

If one country has a trade surplus with respect to another country, then that means that the first country sells more to the second country than the second country sells to the first. In such a case, it is meaningless for the second country to try to have a trade embargo with the first country, because if trade between the two countries is stopped, it is the second country that will suffer more without the goods from the first country.

Any country that has a trade deficit with respect to another country cannot realistically impose a trade embargo on the other country.

A second metric that is useful to understand trade imbalances is the export to import ratio. While the trade balance is an absolute number, and can depend on the sizes of the two economies involved, the export/import ratio (Exim ratio) is a normalized way to understand trade imbalances. If Russia’s Exim ratio with respect to another country or entity (like the EU or Asia) is greater than 1, it means that Russia is exporting more to that country than it imports from it. In other words, Russia has a trade surplus with that country or entity. If it is less than 1, it means that Russia is importing more from that country than it exports to it. In other words, Russia has a trade deficit with that entity.

Let us examine Russia’s trade balances with the world, with different regions, and with other countries The figure below shows Russia’s Balance of Trade (BoT) with the world as a whole and with the Euro Area (data from the International Monetary Fund). It can be clearly seen that Russia enjoys a healthy trade surplus with both the rest of the world and Europe. As of 2020, this surplus with the rest of the world amounted to $106 billion and with Europe amounted to $29 billion. That means Europe bought $29 billion worth of goods and services more from Russia than Russia did from Europe, and the world bought $106 billion worth of goods and services more from Russia and Russia bought from the rest of the world.

|

| Fig. 031. Russia's Trade Surpluses with the entire World and the Eurozone, 2000-2020 |

The next figure shows Russia’s Exim ratios with the World and the Euro region.

|

| Fig. 032. Russia's EXIM Ratios with the entire World and with the Eurozone, 2000-2020 |

We can see that, while the Exim ratio has been reducing over the last 20 years, it is still pretty high at 2020, at 1.5, with both the world and the Euro region, indicating that Russia is exporting 1.5 times to the rest of the world what it is importing from it, and the same with respect to Europe. This indicates that Russia is an extremely important trade partner for Europe as well as the rest of the world, and explains why the rest of the world is extremely reluctant to abide by Washington’s dictates telling them to stop doing business with Russia. Most countries cannot stop trading with Russia. Their economies would collapse. Europe is a wealthier continent than Asia or Africa, so even though Europe’s leaders know that Europe would suffer with a boycott of Russian goods, they are willing to endure it in the short term if it can help defeat Russia in Ukraine. In effect, they are trading prosperity for ideology.

It is also instructive to see how this trade imbalance is distributed between different countries in Europe. This can be seen from the following graph.

|

| Fig. 033. EXIM Ratios for Russia with Various European Countries in 2020 |

This is an interesting chart, and makes us wonder: what is the reason for these huge differences between countries? France and Germany clearly export more to Russia than they import from it; Italy exports as much as it imports; Spain, the Czech Republic, and Sweden all export more to Russia than they import from it; and the other countries in this graph import more from Russia than they export to it. The examples of the Netherlands and Norway are particularly interesting, because both countries are energy-rich. The Netherlands has huge gas fields at Groeningen, and Norway is a huge energy surplus country. What could they possibly be importing from Russia?

To understand these differences, it helps to look at a breakup of the import and export numbers. The Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC) at MIT helps us do this. Let us look at the details from Norway.

|

| Fig. 034. Breakup of Russia's Exports to Norway, 2020 ($1.1 Bn) |

What we see, contrary to the stereotypes have been fed in popular media, is a very mixed picture. About 20% of energy-rich Norway’s imports from Russia are crude oil and refined petroleum (diesel and petrol), about 5% is natural gas (“petroleum gas”), and about 2.5% are coal-based products, including raw coal. Fuels only form 27.5% of a total import bill of $1.1 billion, or about $303 million. A wide variety of items comprise the remaining $800 million in the list, some of which are raw materials and some of which are finished goods: about 16.3% is rapeseed oil; nearly 10% is raw aluminium; nearly 5% is nickel matte, an intermediate metallurgical product (nickel sulfide) in the processing of nickel ore; ammonia (6.5%); soybean meal (2.3%); fertilizer (around 1%); wheat gluten (3.3%); rubber tires (3.1%); carbon-based electronics (0.64%), special-purpose ships (1%), prefabricated buildings (0.83%); refrigerators (0.32%); and a host of other items form the balance. The presence of so many non-fuel related items tells us that when US Senator John McCain called Russia “a giant gas station,” he had no idea what he was talking about. Russia is a diversified economy with much more than gas and oil to it. As already mentioned, it has a strong manufacturing sector.

The Green Transition and the Role of Gas

The obvious question one would have on reading the previous paragraph is why exactly a country like Norway, with extensive oil and gas reserves, would even import oil and gas from Russia. The answer lies in Europe’s persistent efforts to decarbonize over the last 30 years – a journey in which cheap Russian oil and gas have played an oversized role. Simply put, cheap oil and gas from Russia has fueled Europe’s transition from highly polluting coal to green technologies, such as wind and solar energy, by cushioning the impact of the transition. Indeed, if one looks at the percentages of power produced in Europe by different means over the last 30 years, one sees that the share of renewables and biofuels has gone up dramatically, whereas the share of fossil fuels has dramatically dropped over this period. Russia’s supply of cheap gas as a transition fuel has been crucial to this transformation.

.png) |

| Fig. 035. Proportion of Various Means of Energy Production in Europe, 1990-2020 |

Green technology costs money to develop, and the incredibly cheap rates at which Russia has been supplying gas to Europe has meant that even energy surplus countries like Norway could start investing in green technologies. Today, only 58% of Norway’s energy comes from fossil fuels, as can be seen from the figure below. (Source for data: The European Commission’s Eurostat website.)

|

| Fig. 036. Percentage Breakup of Norway's Energy Sources, 2020 |

As seen from the previous image on Europe’s primary energy production over the last 30 years, the greatest reduction has been in the use of highly polluting coal, the use of which has gone down from 13,000 PetaJoules (a Joule is the Système International, or SI (International System), unit of energy; one Petajoule is 1000 trillion joules) to about 3,000 PetaJoules. This can also be seen in the graphic below.

|

| Fig. 037. The Decline of Coal in Europe Over the Last 30 Years |

Essentially, cheap Russian gas has helped Germany completely phase out coal, and has reduced overall coal consumption in 2020 to 20% of the levels that were consumed in 1990.

Russia has made Europe’s transition to a green economy possible.

However, the journey is as yet incomplete. Even with all this help from Russia, the adoption of renewable technologies in Europe is still very inadequate, as can be seen below.

|

| Fig. 038. Fossil Fuel Dependence of Major European Nations, 2020 |

While a couple of countries in the chart above (Finland and Denmark) are close to the 40% level of renewables adoption, many are still in the 10%-20% range of adoption. Fossil fuels still loom large over the European landscape. And, as we shall soon see below, Russia is a huge part of that fossil fuel dependence. It is the economic advantage that Russia provided Europe with its supply of cheap gas that made even this 10%-40% dependence on renewables possible, but that transition clearly still needed a few decades to be complete. The present war, brought upon by European refusal to accept Russia’s legitimate concerns about their encirclement by NATO, is going to set back three decades of progress in Europe’s move to a green future. Natural gas is an essential part of that transition, and that is why wise German leaders like Gerhard Schroeder and Angela Merkel worked closely with Russia to build, first, the Nord Stream 1 gas pipeline, and later, the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline – which Germany has now foolishly abandoned under American pressure.

That is why hopes of a rapid transition from fossil fuels to renewables to overcome Europe’s dependence on Russia in an extremely short time frame are overly optimistic.

Destinations of Russian Exports and Origins of Russian Imports

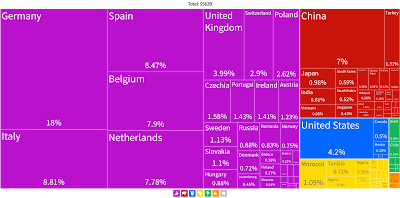

We can investigate where Russia exports the majority of its goods and services to. This can be seen in the graphic below. Most of Russia’s exports in 2020 flowed to Europe, with a value of $160.9 Bn. Closely following Europe was Asia, with $138.8 Bn. The other continents’ shares are small in comparison.

|

| Fig. 039. Breakup of Russia's Exports by Destination Continent, 2020 |